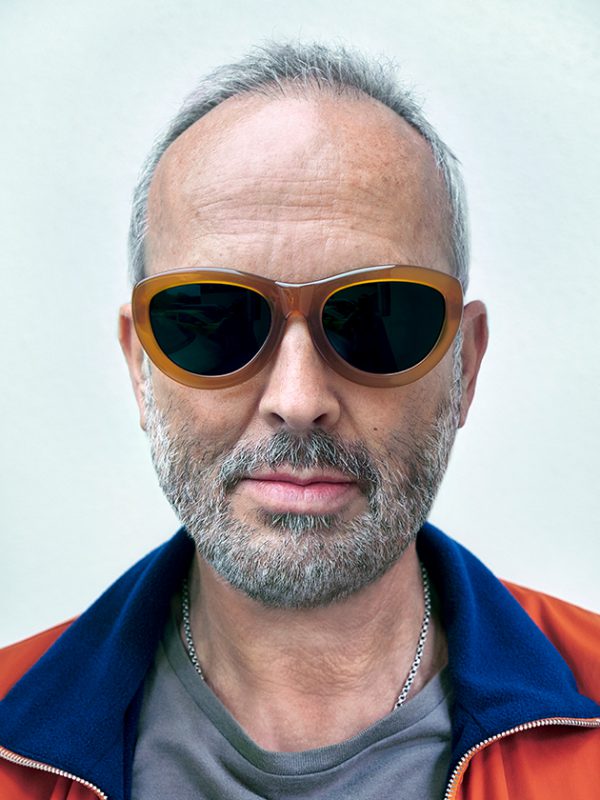

A World Gone Mad by Steffi Kammerer | 2nd March, 2018 | Personalities

Austria’s best known living artist Erwin Wurm has reinterpreted the art of sculpture with his viewer participation pieces. Last year, he represented his home country at the Biennale in Venice. Wurm is a master of the bizarre and paradoxical who comments on our age and affluent societies with a mischievous wink. He celebrated his breakthrough in 1997 with the One Minute Sculptures. Since then, Wurm’s wacky works of art have been on show at many hundreds of exhibitions worldwide.

Obese cars and houses, office workers with asparagus sprouting from their noses, museum visitors in unfortunate predicatments, turned into sculptures… Erwin Wurm is a sculptor with a keen eye. Nothing and no one is safe from his subtle sense of humor. His works of art are created on an estate close to Vienna, where Wurm and his family live in an old house that he renovated with great care. Next door are the high-ceilinged buildings in which he works, supported by half a dozen craftspeople. The five hectares of land belonging to the estate provide enough space for a large number of Wurm’s sculptures, fruit trees and grazing sheep.

“Questions are my daily bread, as are the

doubts and indecision I feel until I finish a piece.” Erwin Wurm

Mr. Wurm, how do you come up with ideas? When you’ve been doing this for several years, you know how it works, how to conjure up ideas. I am trying to get close to reality by using concepts like the absurd and the paradoxical. Seen from these perspectives, you quickly realize how crazy our world is. That’s why I don’t have to get myself into an altered state, get drunk, take drugs or meditate. Instead, when I focus and think about how to develop the work, I experience something like brainstorming. I keep working on the issue, and at some point the ideas come to me. Or not … (laughs) The more you work, the more inspired you’ll get. Most of the materials I use I find right at hand: sausages, pickled gherkins. That’s what I grew up with.

What about the “Narrow House” sculpture, your parental home squeezed into a building just 110 centimeters wide. How did that come about? That was a more lengthy process. At first I was frustrated that I had only been given such a narrow space to work with (Editor’s note: for an exhibition in Beijing in 2010). Initially, I felt like canceling, but then I thought: “Make what restricts you the subject of the piece.” That started several trains of thought. Which house should I showcase the interior of? Eventually, I settled on my parents’ home. It is the only house I know really well. In addition to this, many of my works have been about my parents, my father in particular. The house was built in the 1960s when society was still restrictive. My father was a police detective and we were still beaten at school. All this influenced the piece. I wanted to make the narrow house really narrow. Not in an abstract way, but with photos, curtains and wallpaper from that era.

Do you work on more than one project simultaneously? Yes, I work on many at the same time. When pieces leave for an exhibition, my workshop suddenly feels very empty. I don’t like this state of emptiness, so I keep working. That’s why there’s actually always work going on, except in the depths of winter.

Are there subjects that are beyond the scope of sculpture because you cannot get the work out fast enough? I usually don’t react to events directly. I have tried this a few times, but at the end of the day, I don’t see myself as a political artist. And I don’t want to be one because it would sully my work. I deal with social issues, certainly: the disintegration of truths and established standards. Physical cash will disappear at some point in the future. And we are in the process of giving up our freedoms, of becoming ever more transparent. Everyone just looks on and thinks it’s normal. There something not quite right there. After all, our time is one of uncertainty. We are in the process of losing our last certainties. The enlightenment, one of Europe’s greatest achievements, is getting more and more blurry, due to resurgent patriarchal structures. These are all topics for discussion. I ask questions of society. And I create works of art that ask questions, that assert themselves in this crazy world and that themselves are, to some extent, crazy.

Is it your intention to be provocative? No, what interests me are strong images. I believe in creating things that are memorable. For a recent exhibition, I designed word sculptures for which I invited people to climb on a pedestal and to say one or more sentences, for instance: “A football-sized lump of clay on a light-blue car roof.” You hear the sentence, visualize it, and that’s the sculpture. I like that. I plant an image in people’s minds as though it was a surgical procedure. Only just spoken and immediately it’s in your head. I always try to differentiate myself from artists who use pathos. Pathos makes people feel small, because it is intimidating. Instead, I believe in the marginal, the incidental, the ridiculous and things that make you feel desperate. In the end, what defines our existence is our relationship to humanity as a whole and to history. Compared to them, we are tiny. This discrepancy is something we have to live with. That’s what I am interested in – not the most recent nonsense spouted by Donald Trump or Angela Merkel, for that matter. I don’t want to comment on that. I am interested in absurdist theater, that’s why my work is created this way. Humor is only a part of that which is paradoxical. Humor is also about liberation.

Is humor helpful in a crisis? When your back is up against the wall, laughter won’t get you very far. But if nothing else, being conscious of the fact that everything is relative is helpful.

Does that mean that you find comedy in your everyday life? Yes, I do. I often find myself ridiculous, but others, too. That’s something that does make me laugh. But I don’t find comedy in tragedy, or in the last of the big, important subjects like life and death, and loss. But I do find it in the things that surround us every day, in the little acquiescences that take up more and more space. The older you get the more nutty you become.

ArtFacts.Net puts you at number nine in their ranking of living artists. What do you think of that? I don’t take it too seriously, but it also pleases me.

You are the ultimate authority, of course, when it comes to your work. Do you always know when a work of art is finished? When I started out, I often didn’t know whether to keep working on a piece or whether that would make it overdone. But now I have learned that it’s a matter of experience and intuition. I am friends with the great writer Fritzi Mayröcker, and you could ask whether one of her poems is finished or not. Maybe it isn’t, but that doesn’t matter. Fritzi made the decision to leave as is, and once the writer makes this decision, the work is finished. The same applies to artists. There are wonderful paintings by Picasso and others that feel unfinished, but that’s exactly what constitutes their quality. I often like things better when they look unfinished. But with “Fat Cars” for example, I wanted to create a full-scale image of a corpulent car, so it really had to be completely finished – perfect.

“I ask questions of society. And I create works of art that ask questions, which are crazy as well.” Erwin Wurm

On a technical level, who helped you get the dimensions right? I was invited to the General Motors plant in Rüsselsheim, where they had huge 3D computers, and I was free to experiment for three days, supported by the technicians. But back then, in the year 2000, computers weren’t powerful enough to create anthropomorphic shapes out of the body of a car. So we did it ourselves. The “Fat Car” is an actual Porsche, which we glued polystyrene onto. We trimmed, ground, smoothed out and polished the plastic, and then spray-painted the whole thing. All that took four months. In the beginning I was there the whole time. The decisions about the shape came only from me. I also did part of the work and supervised the process every day. You cannot do this any other way. If you give up control, things will work out, too, but the end result won’t be what you wanted.

When you are trying to perfect a fat car, for example, do you sometimes think: What am I doing? Have I taken a completely wrong turn? I work on other projects simultaneously, but it’s true, these questions are my daily bread, as are the doubts and indecision I feel until I finish a piece. I have experienced moments like this again and again. I still remember creating the first One Minute Sculptures in Bremen in 1997. I had serious doubts back then. Were they any good? I just didn’t know. Then the catalogue sold out quickly and I was asked: “Did you know that people in England and America find your work interesting?” That was very, very surprising.

Do you sometimes abandon works halfway through? Yes, I’ve thrown many things away. It’s important to do that. For example, I had wanted to use modern architecture as the starting point for the first “Fat House.” It was the Villa Müller by Adolf Loos, a tiered building with a flat roof. I had finished the model, but it was only when I made the full-scale fat sculpture that I saw it looked like a bouncy castle. The only thing to do was to throw it away.

What kinds of reactions to your art please you? Not “Oh, that’s funny!” That irritates me because it’s reductive. Otherwise, I don’t really care about the viewers. I’m interested in the work. And I’m interested in the opinions of my colleagues and of the few other people I choose to listen to.

How did you build such self-confidence? When I was a young student, I read and went to see everything. I looked up to the masters of literature, philosophy and the arts, but was unable to connect with them. They were up there and I was down here. I only succeeded when certain events in my personal life made it all less important.

Are you referring to the death of your parents and the divorce from your first wife? Yes, I spent a year and a half not working at all. After that I didn’t really care much about anything. Then I created the One Minute Sculptures. I no longer had this desire to make “good art,” so there was some detachment. You often see that people who know so many great pieces of art cannot break free from them. They end up copying them and can never create a world of their own. They make excuses and talk about posthumous success. I didn’t want to end up like tha.

What alternative career would you have chosen?Even as a student, I used to think that if I couldn’t start make a living from my work quickly, I’d stop. Maybe I would have become a gallery owner, I don’t know. It’s bound to have been something related to art. Works of art are so life-enriching, but you don’t necessarily have to make them yourself.

Many artists suffer for their art. I do, too. You suffer when you want to create something extraordinary or great, but don’t succeed. Look at Alex Katz, he has created something that no one else has been able to replicate. So you suffer, because you don’t succeed in doing the same.

But now you’re world famous. Are you sometimes afraid that your success will one day come to an end? I have been doing what I do for 40 years, so I’m not worried. There is always the fear of making bad art, every day, really. It’s a constant struggle. But I have now received so much validation that I possess a certain amount of basic confidence. There are works of mine being exhibited in all major museums, so I don’t have to be fearful. They’re not going anywhere. But who knows if I’ll ever be able to create more pieces as good as “Fat Cars” or as “One Minute Sculptures”?

What was it like growing up with the last name of Wurm? (Editor’s note: Wurm means worm in German) It was just a given.

Were you teased? Of course. I told my sons we could change their last name, but they didn’t want to.