A Symphony of Color by Eva Karcher | 2nd March, 2018 | Personalities

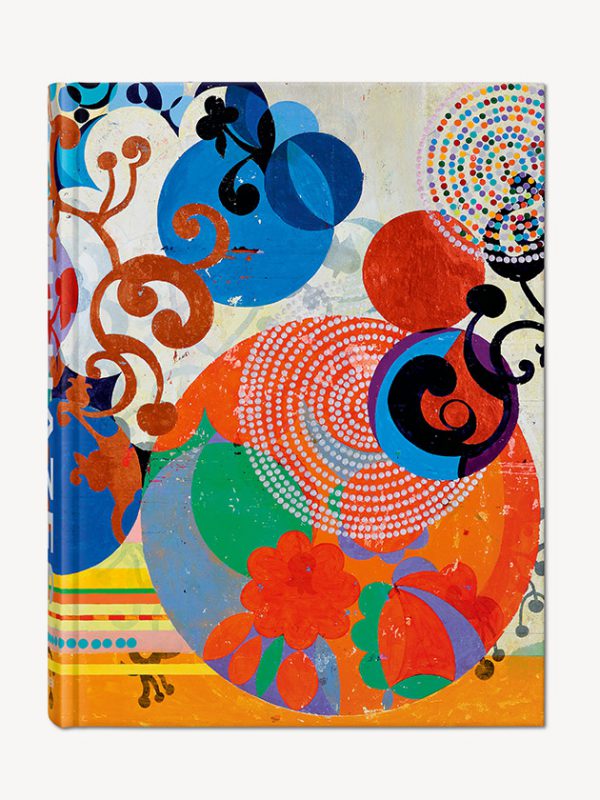

Beatriz Milhazes’ huge, highly decorative paintings have brought her international fame. Art book publisher Taschen celebrates the Brazilian artist’s work in its stores – and has now also launched two limited editions of a new, outsized monograph. For Milhazes, painting is “a perpetual challenge.” Her stylistic mix of foreign and Brazilian motifs, shapes and colors is unique.

We’re in Florida for Art Basel Miami Beach, sitting on the patio of the Como Metropolitan Hotel. Beatriz Milhazes is wearing a cream-colored summer dress with little puff sleeves, gold creole earrings, several gold chains with pendants and rings on almost every finger. “I love flamboyance – and not just in my paintings,” she says. Despite the helicopters whirring overhead, Brazil’s star artist is completely focused.

Ms. Milhazes, you live in Rio de Janeiro rather than São Paulo, the cultural capital. Why? What’s so unique about Rio is the mix of megacity and tropical landscape, ocean and beaches, mountains and forests. It’s also where I was born. My studio is next to the botanical gardens, not far from the Atlantic Forest. I’ve always loved painting, even as a child. It was omnipresent in our house because my mother was a professor of art history. But my father’s a culture lover too; he’s an attorney. Nevertheless, I initially studied social communication and even got a degree in it. But I didn’t see myself becoming a journalist. Then my mother suggested I go to the art academy because I had a good instinct for color. Even after all this time, I’m still grateful for her intuition.

So you studied painting? Yes, that was clear from the outset. In 1985 I saw a painting by Henri Matisse for the first time and it touched something deep down inside me. Analyzing his brushstrokes made me realize it’s OK to make mistakes. But it took me a while to realize how difficult a medium painting actually is. When you’re standing in front of an empty canvas, you have to forget everything you’ve ever learned about composition and technique. Painting is a perpetual challenge. It’s not something that is, it’s something that comes into being. It’s a symphony of colors that I’m after. If a picture doesn’t strike the right notes, it can’t seduce anyone.

Is that what it’s supposed to do? That’s what it has to do. I’ve explored my native country’s cultural heritage in great depth: the traditional costumes and jewelry of the colonial period, the fabrics, ribbons, frills, chains and beads, traditional arts and crafts, indigenous tribal art, carnival folklore and the Brazilian Baroque. I’ve always been fascinated by the way Brazilian culture revels in gold and splendor, its exuberant use of circles, arabesques, garlands and rosettes in ornamentation and its over-ornate architecture. It was this sumptuous culture I wanted to merge with my painting, as well as Brazil’s special light and the tropical vegetation.

And that means using lots of very different shapes, colors and elements? That’s exactly what Brazil is: a culture full of extremely conflicting influences that have intermingled. I think what’s really Brazilian about my art is the freedom I give myself to combine essentially incompatible elements in all sorts of new variations.

Like the way you’ve been taking pieces of candy and chocolate paper, painting them and sticking them on canvases since the turn of the millennium? Oh God, I spent years eating chocolate for those wrappers and condemned my friends to the same fate! (laughs) That’s a good cue to talk about my technique. The work processes themselves are crucial to the results.

You developed your own collage technique, right? Yes. It was all about combining two- and three-dimensionality. I started on the collages in 1989. On the one hand, I stuck fabrics and bits of paper on the canvas and painted individual areas by hand. On the other hand, I started painting motifs on plastic films, letting them dry and then sticking them on the canvas. When I pulled the film off, the motif I’d painted was left behind on the canvas. That allowed me to preserve the intensity of the colors, their metallic gleam and fluorescent brightness. Another very important aspect was that I could define every shade precisely as I wanted it. It also allowed me to combine my motifs in an endless series of new transparent layers, a bit like the metamorphosis of plants.

Plant shapes and flowers are just as key to your vocabulary as the little hearts and crochet patterns of folk art, microorganisms from the realm of biology, the stars and spirals of astronomy and geometric symbols. What is it that connects all these different elements? My imagination. I never copy anything; instead, I translate the atmosphere of a motif into my own visual language. That’s probably why my work manages to fascinate people from different cultural backgrounds. They find something in it that has links with their own culture.

So you used Brazilian ingredients to develop a global visual language? Not only Brazilian ones. There are lots of links to European culture and American pop art too. I went to New York in 1994. Feminism reigned there in those days, and to start with I was only offered exhibitions that either only featured women or only Latin Americans. I refused to take part – and it was a good decision because it meant people perceived me as an artist right from the beginning rather than seeing me as a feminist Latin American artist. The West is only gradually beginning to appreciate the significance of female artists from Brazil – women like Lygia Clark, Mira Schendel or Tarsila do Amaral. Tarsila is one of my greatest heroines! In the 1920s she and her partner, the writer Oswald de Andrade, were the stars of the São Paolo art scene. In a manifesto, Andrade propagated the concept of cultural cannibalism, a radical mix of foreign and domestic styles. That’s exactly what I do.

But it’s not about the mix per se? Oh no, that would just end up being random. All the references I incorporate – the tropical colors, the rhythms of the shapes – are connected with my search for what constitutes our humanity. What’s our most profound human longing? I think it’s spirituality.

And our desire for beauty? The two go together. Beauty has to do with spirituality, it stands for fantasy, intimacy and familiarity. For me, flowers are the primordial symbol of beauty’s diversity and the relationship between nature and culture. Flowers symbolize both joy and pain, we use them to celebrate birth and to adorn our graves. In my house they’re all over the place – especially orchids. I even see beauty in their transience.