The Forbes Legacy by Steffi Kammerer | 1st September, 2017 | Personalities

At times, Malcolm Forbes owned more Fabergé eggs than the Kremlin. He celebrated his 70th birthday with the who’s who of politics and show biz at his palace in Morocco, and he made Forbes a worldfamous business magazine. Kip Forbes and his four siblings have continued their famous father’s legacy and are still busy divvying up their inheritance. A visit to Far Hills, New Jersey, where the Forbes family has resided for nearly 70 years.

He is the third of five children. “The happy medium,” says Christopher Forbes, whom everyone calls “Kip.” He is sophisticated, polite, charming – and seems unusually content and relaxed for someone this wealthy. Kip picks me up from the railway station in a small car; later, he makes tea in the kitchen, looking around for cookies. He is an art historian, an expert in English 19th century paintings. His main job is that of vice chairman of the Forbes media group and he is always on the road. In between trips to Paris and Jakarta, he returns to the place he has lived all his life: the 172.000-acre Timberfield estate in Far Hills, New Jersey.

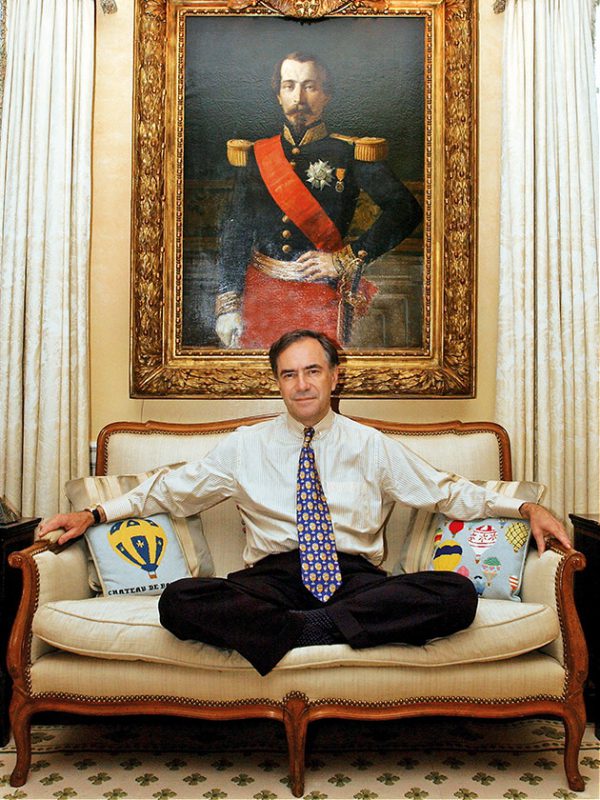

Seven houses form part of an estate that is so vast you have to take a car to get from one house to the other. Malcolm Forbes passed away in the largest of its buildings in 1990 while taking an afternoon nap after returning from a trip to London. Kip’s father – never one for half measures – had chosen the rural environs of Timberfield as his sanctuary. Here, he would mow the lawn on weekends after flying across Egypt in his own, sphinx-shaped hot-air balloon. A father like this can drive his children to despair. However, just like Kip Forbes, his three brothers – Steve, Robert and Tim – and his sister Moira are grounded, industrious individuals. Steve ran for U.S. president twice, but never made it past the primaries. Kip, on the other hand, has a title that one cannot make a bid for: he is an officer of the French Legion of Honor. This is how the French government thanked him for his long-standing support for the Louvre museum. As a member of the board of the Ellis Island Foundation, Kip also helps to preserve the Statue of Liberty, and has been supporting the reconstruction of the Berlin City Palace. He once sat on the boards of half a dozen prestigious museums, but has slowly been scaling back his involvement. These days, “letting go” is the new family motto. In fact, they’ve been downsizing for years. As a result, the famous Forbes magazine, which is celebrating its 100th birthday this fall, was able to survive the recent crises. The family has sold the 70-hectare ranch in Colorado, the Moroccan palace where Malcolm Forbes hosted the party of the century, the “Highlander” yacht, the huge, old residence in London, 75,000 toy soldiers and a private island in the Pacific. Added to that, the family’s unique collection of Fabergé eggs, which sold for 100 million dollars. Kip’s Victorian paintings also had to go, and their sale raised 27 million dollars. At the time, he told a newspaper that he would not be attending the auction because it was all too sad. Nowadays he is good at letting go. Last spring, he parted with his personal treasure, his Napoleon III collection: 2,000 works of art, manuscripts and photographs. Kip started collecting objects connected to Napoleon III when he was a teenager, after his father had given him a portrait of the former French emperor as a present. The family is, however, planning to hold on to the chateau, magnificent 17th century Balleroy Castle in Normandy, which was the inspiration for the palace of Versailles. It had been falling into disrepair for many years when Malcolm Forbes bought it in 1970. Kip refurbished the building over the course of two decades and now stays there roughly five times a year. The rest of the time, he lives in Timberfield with his wife of 43 years, Astrid, who is a scion of the German aristocratic family Heyl zu Herrnsheim. Their daughter, son-in-law and three grandchildren live in the neighboring house.

“The happiest legacy is that we all get along.” Kip Forbes

In 1989 your father dedicated his book More Than I Dreamed to you. He wrote: “To son Christopher, whose friendship, love, genius and wit have been instrumental in making this life more than I dreamed.“ Please tell us about your special relationship. My father had a special relationship with each of us children. Because each of us inherited a little bit of him. More Than I Dreamed was about a lifetime of collecting. That’s why that book was dedicated to me – because of the shared passion. I was very touched. I had no idea – one day he gave me the proof of the page and I, of course, burst into tears.

What was it like to have Malcolm Forbes as a father? When we were younger he was the disciplinarian. My mother only had to say: wait till your father gets home, and we would start to behave again. In those days you were still allowed to get a spanking. But it was not like he was taking a belt and whipping us, it was more the psychological buildup. And then, as we got older, and had dinner with our parents and got more and more involved with them, one got to know him as a fun and interesting person who was happy to engage each of us in our particular interests.

So he was actively involved? He often went on longer work trips but otherwise he was around. When we were younger we always had to go to church on Sunday and that was quite a production. My father, proud of his Scottish heritage, made us wear kilts. And we had to learn to play the bagpipes. Twice a year we could get our mother to conspire with us and say the kilts were at the drycleaner, but other then that, it was all your friends snickering about you wearing a skirt. It was certainly never boring when he was around! He was a dominating presence. When I was an undergrad at Princeton he allowed me to start assembling this incredible collection of English 19th century paintings. Simultaneously, he was also buying incredible documents that were of interest to my two older brothers. He started collecting toy boats and toy soldiers, some contemporary art. You literally never knew what he was going to come home with next. Some of it was stored here, some was at the offices in New York, some was on the boat, some was at the ranch in Colorado, some at the island in Fiji, some at the chateau in France. It was all over the place. There was never a lack of walls. Which, now, as we are continuing to downsize, I find challenging.

Who did the inventory? Or did he know where everything was? No, he did not even pretend to know. My first job was to be the curator of the collection. Then, when I graduated and had to start the fine art of selling advertising, we hired a professional curator. There is still so much stuff. The books alone: there are masses in the library and in the bomb shelter, all initialled and dated by my father. Or take that table over there: you multiply that by dozens. But we are whittling our way through it, slowly but surely. I know that my daughter is grateful for the epiphany I had that it was time to start getting rid of things so that she wouldn’t have to send it all to the dumpster or auction. At some point we will have a tag sale here at Timberfield.

Did you find it difficult to part with some of those things? In the first sales after my father died, it was difficult. Now it is almost cathartic, one almost cannot wait to get rid of things. It sort of feeds on itself. At first I was sentimental: this belonged to this person and this to this person, but now I just think weg, weg, weg (GG: that’s German for “out, out, out”).

You had some serious festivities at this house. The 70th birthday of the magazine was at Timberfield and yes, that was heavy duty. There were 40 or 50 helicopters parked in the big field. For the magazine’s 75th birthday we went to Rockefeller Center and Radio City Music Hall and former President Reagan was there with President Gorbachev.

This year will be the big one: the 100th anniversary of Forbes. How will you celebrate? There will be a special issue of the magazine and stuff on the web. And then I assume in September there will be a special event.

When you think about your childhood, what images come to mind? Playing monopoly and the occasional earthquake if anybody was not happy with where the game was going. The most bonding experience was driving across the country to Wyoming in a station wagon. My parents, five children, my sister’s nanny and two dogs. In those days you didn’t have car seats for children, so we were all crawling all over the place. I was in the back making sandwiches for everyone. We used to drive out in the beginning of the summer and came back in the middle of August.

How close are you and your siblings today? We all are still happily close. We have family meetings once a month, either by telephone or in person. We don’t always agree, but we make a decision when it’s about the business. Any dissention within the family never impinges on the business. This is very important.

It sounds easy, but so many families fail at that, especially when there is substantial money involved. You must be doing something right… I would say my parents did something right – the happiest legacy is that all of us do get along. It does not mean we are best friends or the inlaws are all best friends.

But you still talk to each other… Exactly. The sense of family is stronger than these forces that can divide you – with money usually being the first one.

How did your parents do it? They were both so different: having this quiet, sweet, understated mother and this outgoing, complex but larger- than-life father gave us a good balance. We are all products of both and that’s why we all get along.

Did they instil a sense of dynasty or legacy in you? I don’t think one really has a sense of dynasty or legacy. But checking out of places and hearing someone say: “Are you one of THE Forbes?,” that was always a nice thing. I know that some of my siblings are less comfortable with it – but you don’t get to pick your parents and in the lottery of life, I think we got a pretty good deal. I remember going to the office the very first time as a kid; getting off the elevator and seeing cut in the linoleum on the floor: Forbes. And I thought: wow, that is cool.

Did you feel an obligation to live up to the name? No. But of course one never wants to embarrass anybody. And it was not like being a Hearst or a Getty or a Rockefeller, it was a much more modest brand. But it boomed under my father. We saw that happen.

Did you and your siblings ever go through difficult times together? Oh yes. There can be divisive moments: when you are settling an estate or when we made the decision to sell the majority interest of the company. But that’s the point of meetings and why it’s important to keep talking. When you make a decision you have to make sure that everyone is on board.

What helped you in really tough moments? When it came to the business we brought in outside mediators. They were a fabulous combination, one is a lawyer, one is a shrink. They were great at helping us understand that this was a process. You cannot just rely on the informality of getting together. That institutionalized the idea that you need to talk on a regular basis because then things don’t accumulate. When it came time to divvy up the things in this house, our spouses could talk to us beforehand and say what they liked. But then it was just the five of us sitting in the house. We each had a list of ten things that we particularly wanted. There was one painting that was on three lists, so we had to draw straws for that. After getting rid of everyone’s top 10 we started going through the house. Again, with a system in place: whoever went first would be last the next time. We chose regardless of value. We had the appraisals, then we totalled everything up and in the end we levelled it off with money. The five of us came up with that system. It was based on knowing which problems our parents had had with their own siblings, especially my mother, who barely spoke to one of her sisters. Our parents had said: you all have to figure out a way to do it. So we thought of a system that was impartial. Being able to work formulas like this out is very important for family comity. We are lucky because all five of us were from the same parents. It gets more complicated when there are halves involved. It’s far more nuanced and complex the more often one’s parents have married and the more extended even the immediate family is.

So your parents made you aware of potential problems early on. Yes. My grandfather left equal shares in a way that made life difficult, whereas my father left us all very generous pieces of the company but left more voting stock to Steve (and if something had happened to him, it would have been Tim, my youngest brother) so that somebody was clearly in charge of running the business. Being fair is not necessarily the best way to move a company to the next generation. So Steve had a controlling vote. Even if four of us disagreed, somebody had to make a decision. It was not something we found out about in a lawyer’s office after our father died, we always knew. And we understood the reasoning behind it. If anything had happened to Steve, Tim was obviously the most qualified to decisively run the business.

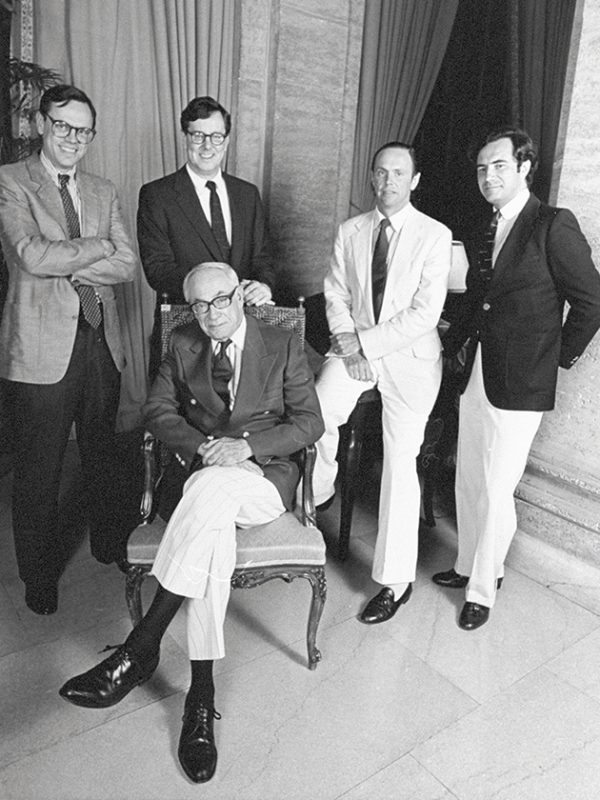

You were not interested in it at all? I had no competence to run the business. Even in ad sales I could be charming but I was not a very good closer. The more candid one is and the more transparency there is, the easier. We are lucky that it worked. Was everyone totally happy? No. But there were no surprises. I could not argue that I could run the company better. It was Steve’s passion. One of the remaining issues that could have been contentious recently was family portraits, conversation pieces that all five of us were in. They were painted by two different artists. The artist who did the first two died and another one did the other two. The first two painting are fairly valuable. So who gets what and how do you cover the discrepancy? Then there were four paintings and we are five children. But there were sketches and also a portrait of my mother. So we worked out a formula. We managed. We did not need the lawyer.

One of the portraits shows you all in the courtyard in the 1950s, another one depicts you in the very room where we are sitting now. My parents bought this house when they were expecting me. It’s the house I was delivered to from the hospital. It has been a wonderful sense of continuity, not having changed my address once. We did everything here. My parents were very laissez-faire compared to my friends’ parents. We used to play soccer in the front hall and there was a pingpong table over there. We were allowed to play havoc here, we made tunnels out of the sofa cushions, we always had friends over. This estate I inherited outright. My father again thought you can’t chop it up. Just as Steve got the majority of shares, this was left to me. Everyone knew this. My father did ask my youngest brother, because at that point he had one child and his wife was pregnant with another. But my brother said, you always promised that to Kip and I don’t want it. Eventually we will probably put the house on the market, but right now there is no urgency.

You seem very good at letting go. I have a wife who saw everything disappear from one moment to the next on one side of her family.(GG: her mother was a Bismarck). It puts things in perspective.

Do all your siblings still live close by? Not anymore. Number 2 brother retired and is living in Palm Beach. My oldest brother is just down the road. Number 4 brother has a house not too far away. My sister is in Pennsylvania.

You refer to each other by numbers? It makes things easier. But when we talk to each other, we say our names.

You are an expert on Napoleon III. How are the Forbes different from the Bonapartes? I cannot think of too many points of overlap. My grandfather was short, so I suppose he and Napoleon had that in common. And he created a successful business. My father did not succeed in quite that way: none of us got to be king.

When people collect, there is this adrenalin rush. Do you still feel that? Oh yes. Even as we speak there is an object coming up. The other day I did break down. A painting by Sir Edwin Landseer, who was amongst Queen Victoria’s favorites.

What about Fabergé auctions? I still find them interesting. Mr. Vekselberg (the Russian billionaire who bought the Forbes collection) kindly invited me to be on the board of his museum and I thought it would be nice to be involved with the eggs again. To be able to see the babes again!

But you no longer feel the urge to own them? No, one does not really own anything. One is the temporary curator. A trustee for a time. Great art will live much longer. Even Balleroy, it belonged to the same family for 300 years and now we have owned it for 50 years. But who owns the mountains in Colorado? Who owns Mount Rushmore? They are there for eternity. To have had the privilege to be the custodian is amazing.

How long had you been collecting? From my earliest days. Coins and stamps and comic books, and from there to Napoleon III. He was a lifelong addiction until I went cold turkey. It really is a catharsis. It’s good.