The Rebirth of Miss Gray by Jörg Zimmermann | 4th March, 2016 | Personalities

Seven years ago a “Dragon Chair” by Eileen Gray fetched nearly 22 million euros at auction – the most expensive 20th-century chair since. The Irish designer and self-taught architect didn’t live to enjoy her late fame as she died beforehand, at 98. But today her furniture re-editions and Gray’s villa E.1027 that she built on the French Riviera in the 1920s bring her name and designs back into the spotlight.

We love these places. Magical places where life and love, passion and loss, fame and legend are intertwined in truly dramatic fashion. Places with a history, places with stories to tell. Places that draw on the past to shine in the present. Places like Roquebrune at Cap Martin, an impressive stage set against the backdrop of the French Riviera. This is where the villa known as E.1027 steals the show – along with its creator Eileen Gray.

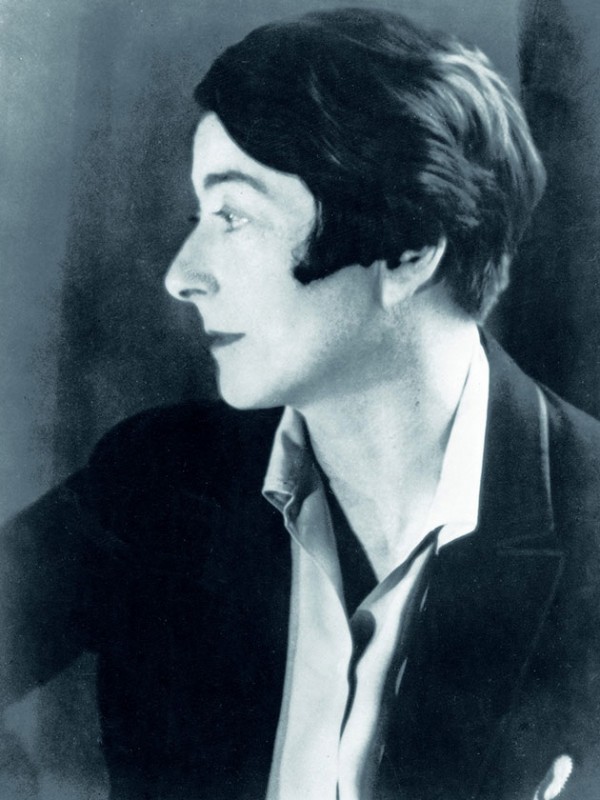

As part of the modernist repertoire, the house overlooking the sea marks an important scene in a play which, even today, continues to cast Eileen Gray in the role of leading lady. She is regarded not just as one of the most important furniture designers and architects of the early 20th century but as the most influential female protagonist of the entire period. For a long time, her name and work were almost forgotten – until, at the end of the 20th century, interest in her superb designs was rekindled and the originals started fetching staggering prices at auction. Eileen Gray’s biography is just as much part of modernist history as it is the story of an independent character (find out more in Eileen Gray by Peter Adam, published by Schirmer Mosel).

“Everyone in the house should be able to find a quiet corner where they can relax.” Eileen Gray

When Eileen Gray travels to Paris with her mother to see the Exposition Universelle in 1900, the modern world reveals itself to the 22-year-old Irishwoman once and for all. Having started out as one of the first female students to attend the Slade School of Fine Art in London, she now falls under the irresistible spell of the French capital. The world’s fair presents all the promises of the dawning century, unmistakably heralding the turning point in technology, society and culture that is about to come. The world and Paris are overflowing with inspiration. Exhilarated by this contagious atmosphere, Eileen Gray sets to work. She soaks up a wide range of influences, although to begin with her work is still dominated by elements of Art Nouveau and Japonism, which is particularly popular in France at the time. The young designer learns Japanese lacquer techniques from Seizo Sugawara and craft skills at the London furniture workshop of D. Charles. In 1910, she begins making lacquer screens. One of her later designs, the “Brick Screen,” is destined to become one of her much sought-after masterpieces.

In the early 1920s, Eileen Gray meets architect Jean Badovici. The young Rumanian is the editor of the influential architectural magazine L’Architecture Vivante and a close acquaintance of some of the most fashionable creative names of the day, including Gerrit Rietveld, Fernand Léger and Le Corbusier. The two become lovers, and Gray enters into this inspiring milieu. The new influences affect her work, gradually changing her design language. The forms became clearer, the lines and materials merge. Industrially produced materials like tubular steel and glass are paired with simple geometric shapes. While Eileen Gray’s design exhibits an affinity with the popular International Style, she develops an independent position on form.

“To create, one must first question everything.” Eileen Gray

With love comes passion – in Eileen Gray’s case, for architecture. Encouraged by Jean Badovici, Eileen Gray devotes herself to her new-found field. In 1926, she buys a piece of land on the Côte d’Azur in his name and sets to work on sketches and models. Her mentor Badovici gives Gray carte blanche to implement her ideas as she sees fit. Working on site, she designs a building that weaves her ideas about design, interior design and architecture into a fascinating whole. It takes three years to complete the gleaming white villa. Gray calls it E.1027, an encoded form of her own and Badovici’s names. The house itself is minimalist and open. Eileen Gray has built her manifesto.

Topped with a flat roof, the L-shaped two-story building has a footprint of 120 square meters. Floor-to-ceiling windows provide stunning views of the surroundings – the green of the stone pines and the deep blue of the Mediterranean. For Eileen Gray, the human experience is paramount, everything hinges on the combined effect of the space and that of moving from room to room. True to her holistic interpretation of design and architecture, Eileen Gray creates all the furnishings for the villa as well. Not just versatile built-in elements, but movable items like side tables, armchairs and lamps as well.

“E.1027 is a masterful piece of architecture.” Oliver Holy, Classicon

Then, in 1932, he separates from Jean Badovici. Eileen Gray builds other houses. Meanwhile, Le Corbusier has become a frequent guest at E.1027. With Badovici’s blessing, Le Corbusier creates seven murals between 1938 and 1939, two of them on the exterior walls of the house. Eileen Gray considers the paintings an affront, a sign of disrespect for her work. She never sets foot in her architectural legacy again.

After Jean Badovici’s death, the house is sold to a relative of Le Corbusier in 1960. In the years that follow, the property changes hands a number of times. It is the scene of a murder, drugs and other excesses chip away at its reputation. Some of the furniture is auctioned, and many of the built-in features are damaged beyond repair. The architectural gem deteriorates. Salvation finally comes in 1999, in the form of the “Conservatoire du littoral.” The government agency buys the building, and once emergency measures have been taken, renovation gets underway in 2006. In 2015, the work is complete: E.1027 has been restored to its former glory. From summer 2016, the house and grounds will be completely open to the public.

Now considered icons of modern design, the villa’s furnishings have not been entirely lost either, fortunately. Historic originals by Eileen Gray continue to be tracked down to this day and are greatly prized by collectors. The re-editions, on the other hand, are much more affordable. A few years before her death in 1976, Gray granted Aram Designs Ltd. of London the rights to her designs. Today they are produced under license by ClassiCon. One of these re-editions, the “E 1027 Adjustable Table” from 1927, was designed specially for Gray’s sister so that she could read and eat in bed more comfortably. Another of the designs in the ClassiCon range is the endearing leather “Bibendum” armchair from 1929, which Gray – for obvious reasons – named after the Michelin Man. The original stood in the E.1027 house, where it provided a perfect spot to relax and take in the vast blue expanse of the sea. JZ