Sublime Journey to the Far North by Wolfgang Gehrmann | 16th June, 2017 | Travel

Summer is the perfect season to navigate the Arctic Ocean and the Northwest Passage. On a cruise, you will encounter polar bears, clarity and silence between Spitsbergen, Greenland and northern Canada.

Until this beautiful midummer’s day the only ice the guests on board have come across clinked gently in their glasses prior to the captain’s dinner. But on August 21, around midday, Thilo Natke, captain of the “MS Hanseatic,” notes down the word “ice” in his logbook – and next to it, the ship’s position: 68° 35’ N, 111° 07’ W. It is where the ship first ventures through a field of pack ice in the Dolphin and Union Strait. Icy shapes of various sizes are dotted around the steel-colored surface of the water and form a bizarre seascape that stretches all the way to the horizon beneath a pale sun. Piercing the arctic air is a percussive symphony led by the scraping and thudding of ice floes against the ship’s hull. “The long-awaited ice brings all the passengers crowding onto the foredeck and into the mess, where they stand in almost reverential silence as the ship quietly glides forward,” notes the captain in his logbook. It is moments like this that draw people to expedition cruises to the High Arctic. Some of them may have had enough of southern summers, while others want to experience the icy north with its whales and polar bears as long as it still exists. Even captains who have navigated the polar waters up to 150 times like Natke are unable to contain their enthusiasm for the ultimate treat that lies ahead: the humbling experience of boundless space, silence, clarity and immeasurable time. The Hamburg-based Hapag-Lloyd shipping company offers summer cruises between Spitsbergen, Greenland and the northern coast of Canada on board its small cruise vessels: the “Hanseatic” and the “Bremen.” Responding to increasing demand, the company has also built two further ships. The routes and schedules are determined beforehand, but the details of each expedition are dictated by the weather, the tides and the ice drift. And by the kings of the Arctic. When the announcement “polar bears in sight!” rings out from the loudspeakers, the ship’s restaurant will empty in a matter of minutes, even during a captain’s dinner. The captain doesn’t mind stopping for an hour or so to allow passengers to observe the bears drifting past on their ice floe. While polar bear sightings are not guaranteed in the price, lucky Arctic voyagers are bound to see whales spouting. They will encounter a minke, humpback or even a blue whale and witness the incredible sight of flukes rising from the sea only to disappear again in elegant slow motion. When watching whales or polar bears it is better to stay on board the ship and observe the majestic creatures from afar. But when walruses come into view, tough rubber dinghies called Zodiacs are deployed so that passengers can climb aboard and observe the third member of the “Arctic Big Three” up close. These tusked and flippered creatures love nothing better than to relax on rocks and ice shelves, and at the most, will tussle with each other for a good spot. Once they’ve slid into the water, the gently giants will allow the dinghies to approach them to within twenty meters.

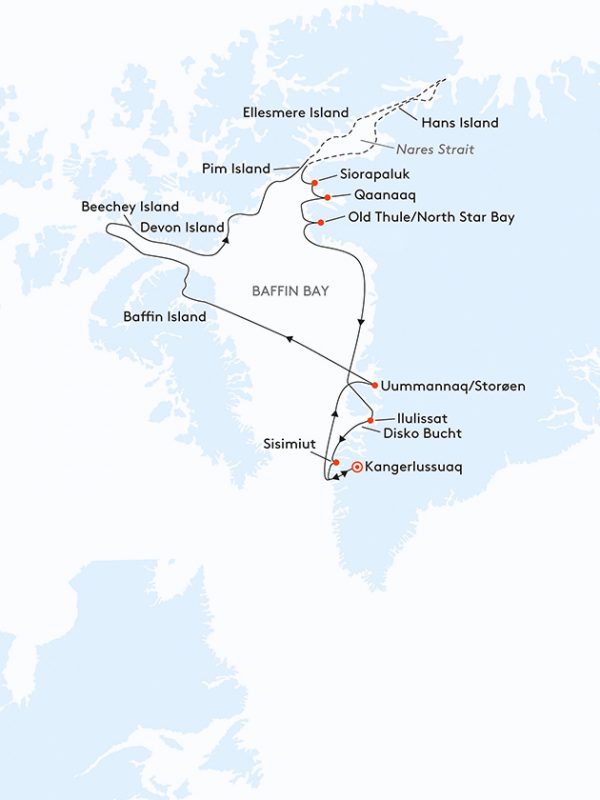

The Zodiacs provide an element of adventure on these polar cruises and allow participants to really get up close to the Arctic. Dressed in thick parkas, waterproof outer pants and rubber boots, some cruise passengers ride across the gentle waves. Thanks to the vessels, the floating labyrinth of newly formed icebergs on Greenland’s western coast becomes navigable. The Jakobshavn Glacier is the world’s most active glacier. In warm years, it advances by roughly 45 meters every day, releasing up to 25 million tons of ice into the sea. The red expedition parkas are ideal for being photographed against the huge, blue icy walls and the bizarre shapes of the silent giants. Fears of Titanic-style incidents are unfounded: the flat Zodiac vessels are not in danger from the ice beneath the ocean surface. Furthermore, the agile mother ship, which measures roughly 130 meters in length and has a draft of only five meters, is able to stay at a safe distance even in darkness and foggy conditions thanks to its radar. As there are no harbors anywhere close, the inflatable dinghies also allow for “wet landings” on beaches. This makes hikes across the tundra possible at short notice, for example if the weather and tides hamper the ship’s progress or if the seaplane transporting the polar pilots is delayed. Such jaunts change one’s perception of scale. The vast expanse of the arctic tundra hones the senses. You suddenly notice small animals more acutely, while modest lichens seem to exude the beauty and uniqueness of a lush spring meadow. On inhospitable Beechey Island, scenic delights are very limited. Three sailors’ graves serve as a reminder of the last expedition undertaken in 1846 by the British explorer John Franklin, who was looking for the Northwest Passage – the sea route from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean via the Arctic. He discovered it, but found himself unable to sail through it because of the ice sheet. Franklin perished along with his 129-strong crew. One of the consequences of climate change is that several years ago, the passage became free of ice – and thus navigable – during the summer months. This allows cruise ships to venture through it without the aid of icebreakers. At its halfway point, in Peel Sound, the passage can still be tricky to navigate because this is where different flows of pack ice meet, creating opaque clusters of vertically tilted floes illuminated by a low-lying sun. So you never really know which of the roughly one dozen Inuit settlements between Baffin Bay and the Beaufort Sea the ship will be able to reach safely. None of them are idyllic places: a few hundred inhabitants, a co-op store, post office, school and a cemetery. Where ice dictates the speed and rhythm of travel, you find time to read. And what could possibly beat The Discovery of Slowness, Sten Nadolny’s magnificent novel about John Franklin’s life? When the explorer gets stuck in the ice for the first time, north of the 81st parallel on a brig called the “Trent” in 1818, Nadolny imagines him developing a fascination with the glittering, icy world and its absolute timelessness. Two hundred years on, Captain Natke’s passengers share this sentiment. Franklin muses that in this environment, no one actually needs a destination anymore. The destination was only a means to find your way here.