The Power of the Streets by Martin Tschechne | 2nd March, 2018 | Travel

Once an innovative subculture, street art has long found a place in galleries and museums. The stars of the scene develop ideas for fashion and design, intervene in urban planning and make millions. But the artists are still committed to one thing in particular – fighting for a better world.

Oh, if only we could meet her! All Barbara needs is a few adhesive letters to transform the German sign “Keep drive clear at all times” into “Racists, keep quiet at all times.” – “No parking” becomes “No thinking,” and a “slip hazard” sign now proclaims “smooch hazard,” its yellow background littered with red kisses. Below a stern sign saying “post no bills,” a second notice on the wall responds: “Your imperious tone hurts my feelings.” Another wall features another harsh riposte: “You’re stuck to the wall yourself, you twit.” Germany’s most famous (and probably most industrious) street artist creates and spreads her subversive messages in Berlin, Dresden, Hamburg and Heidelberg. Yet she remains anonymous. Nobody knows whether Barbara is her real name or even if she is actually a woman. When her witty, often ballsy slogans won her the Grimme Online Award in 2016, she sent a tightlipped stand-in onto the stage to receive it. Although the stick-on letters she uses can easily be removed – and collectors delight in pinching them when they discover an original work by Barbara – German law says that pasting or painting letters onto someone else’s walls is a criminal offense. Viewers’ gratitude for a temporary respite from the daily grind, a moment of reflection or a quick smile are not considered extenuating circumstances here.

“I want to bring beauty and light

into poor neighborhoods, too.”

eL Seed

But the slogan scribbers and bill posters have long since turned what they do into an art form that encompasses a breathtaking multitude of topics and statements and aims to win over devotees. This it has done from Brooklyn to Moscow and Cairo to São Paolo, in Mexico City, Lisbon, Dublin, Dubai, Lagos, Mumbai, Sydney and Youssoufia, Morocco. Los Angeles, New York, London, Paris and Tokyo are its most important centers. There are neighborhood-specific projects, special tours for tourists and very successful street art galleries. In September 2017 the Urban Nation street art museum opened in Berlin. It had 20,000 visitors in the first two months alone. The previous spring, roughly 80,000 art lovers had lined up in front of The Haus pop-up gallery close to Berlin Zoo. Keep your eyes open and you will also find astonishingly creative artists producing utterly skillful, witty statements in cities such as Dresden, Hamburg, Tel Aviv, Vancouver and Genoa. Is the city their playground? A New York subway car, the rear courtyards in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district and the concrete frontages of Parisian suburbs have all been used as canvases for agitation. Is what these artists do somewhere in between smugly marking their territory and calling for solidarity, between shaking some things up and tearing others down? That probably was, and still is, the starting point for many of them. But now the stars of the street-art scene are being celebrated on exhibition walls. They supply collectors like Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie and Eric Clapton. Their works, like those by Banksy, fetch seven-figure sums at auction and they are commissioned by city planners and fashion designers alike.

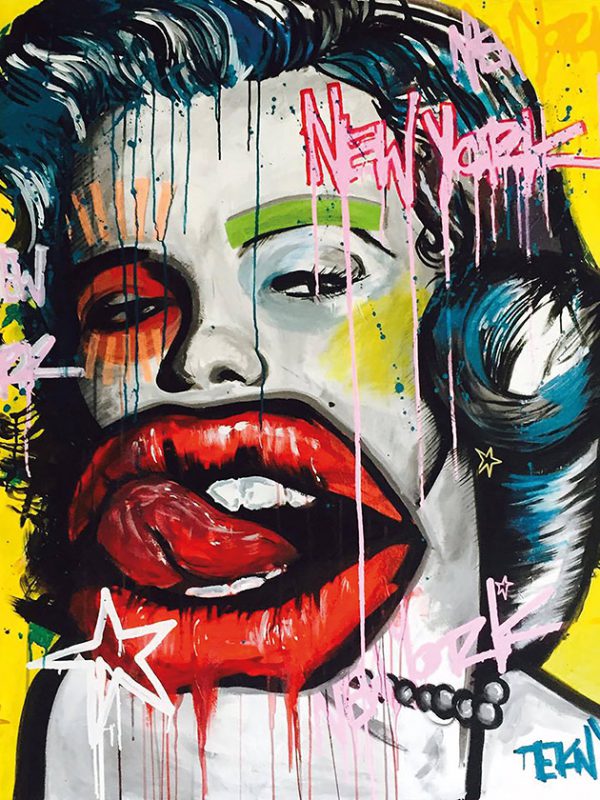

Efkan Irkilata from Kassel, Germany, has never roamed the streets with a spray can in hand. But he takes motifs and tags from graffiti and street art and turns them into murals for clubs, and designs for shirts and leather jackets. Annie Preece from Los Angeles works for Red Bull, Pabst Blue Ribbon and Warner, and also sells her works of art via the Lab Art gallery in her home town. Gregory Siff from New York collaborates with the influential art dealer and curator Jeffrey Deitch and develops projects for PS1, the experimental space at New York’s MoMa, but also for fashion labels like Saint Laurent and Helmut Lang, as well as for Mercedes-Benz. So has street art become gentrified? It definitely has, writes Alain Bieber, a disappointed fan, in Art magazine: “You’ve reached a place you never wanted to be in where everyone agrees that you’re awesome.” The old rule of thumb nevertheless still applies: Art is an intellectual pursuit. It requires knowledge, and grows out of art history and the discourse of a community made up of a select few. It is worthy and educated, but at the same time always in danger of not transcending its immediate milieu. But this art form is different. It pursues other goals, uses other means. International street art is born out of an urgent need to communicate, to transcend borders effortlessly, to reach and inspire others. It highlights injustices in huge letters and loud colors: war, the plight of refugees, turbocharged capitalism, ubiquitous surveillance. It grows out of an aesthetic of the contemporary and the everyday. This art form moves to hip-hop beats and rap cadences. It employs the snappy phrases used in advertising and comic strips, calligraphy, political cartoons, apps and video games, and combines and mixes them all together cleverly. It does this to intercede and intervene, to open people’s eyes, to invite resistance and to influence policy. So is art a forum for social critique? Is that still possible in a time when commercialism lurks around every street corner? French-Tunisian artist eL Seed turned an entire neighborhood in Cairo – home to the city’s Coptic Christians, its garbage collectors and pig farmers – into a large-scale, magnificent symbol of tolerance. He gets teary eyed when he says that he had never before experienced a more profound feeling of community. Irish artist Conor Harrington raises awareness with his epic scenes of physical violence spread out across entire frontages precisely in places where the urban architecture of high-rise blocks, storage buildings and dreary suburban streets is a brutalist act itself. The Canadian artist Richard Hambleton, who passed away last October, made dark corners of New York, Paris and Munich even more menacing with briskly sprayed-on, shadowy figures. Or take Barbara who writes: “Those who have nothing and know nothing set homes for refugees alight.” Bam! Any further questions? She has almost 650,000 followers on Facebook. Barbara and the other artists have taken Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol at their word: Every human being is an artist, said one. In the future, everybody will be world famous for 15 minutes, said the other. Prescient indeed!

Artists like Barbara, Banksy, Harald Naegeli, Blek le Rat, Shepard Fairey, Ganzeer, Futura 2000, the FAILE duo, the #PaintBack initiative, Swoon, Oz and BLU all said: “Great idea. Let’s do it.” But even at first glance, two things are obvious. First, the artists do not meet their fans at champagne receptions held in their honor in fashionable galleries, where guests greet each other with pecks on the cheek, exclaiming “Lovely to see you, darling!” Harald Naegeli, one of the forefathers of the movement from the late ’70s, enigmatically called the “sprayer of Zurich,” was subject to an international arrest warrant. He was promptly detained, extradited and jailed for his art in 1984. Barbara knows exactly why it’s a better idea to put up her art in secret. When, following research worthy of a spy novel, London’s Mail on Sunday newspaper outed Banksy as Bristol native Robin Gunningham, there was an outcry from the street art scene, which felt robbed of their precious secret. “Why did you do that? You have ruined something very special.” Banksy’s graffiti featuring a masked street fighter, who seems to be throwing a Molotov cocktail but is actually holding a bunch of flowers, remains an iconic embodiment of this art of protest and subversion. The huge image features prominently on a wall in Bethlehem and has been reproduced on T-shirts and posters millions of times, as a message of peace. And yet, it remains a symbol of rebellion, an image akin to David taking on Goliath. It just won’t do for the creator of such art to have a conventional name like everybody else. Second, there are many who push their way into the public sphere and onto fireproof walls and frontages with sweeping gestures; many who rephrase the curt commanding tone of caution signs; or who – like American artist Dan Witz – paint a tiny hummingbird onto the sidewalk only to disappear again without a sound. Street art is the opposite of elitist. That is its aspiration and manifesto. Anyone who can hold a spray can or a thick marker pen, who is familiar with the jagged artwork of mangas and anime, can have a stab at it. Most of those artists have to make sure they don’t get caught by the police, but some will make it really big.