From Düsseldorf to the Museums of the World by Martin Tschechne | 2nd March, 2018 | Personalities

Anselm Kiefer, Andreas Gursky and Gerhard Richter all have something in common: They studied at Düsseldorf’s renowned Kunstakademie art school. Martin Tschechne on a 200-year-old institution that can always be counted on to produce artists of international repute, thanks in large part to its strong and demanding teachers.

Fall 1984, Hall 13 at Düsseldorf Exhibition Center. While prominent figures from the international scene – from Marina Abramović to Andy Warhol – were primarily responsible for pulling the crowds, it was mostly young artists from the city itself who, with the two-month exhibition of their paintings, sculptures, photographs and installations, made it abundantly clear that it wouldn’t be long before the whole world knew their names. That’s exactly what happened.

To this day, the exhibitors number among the great names of contemporary art and their works are among the highlights of some of the world’s major collections and museums. They fetch top prices in galleries and auction houses from New York to Shanghai: Gerhard Richter and Markus Lüpertz, Katharina Sieverding and Jörg Immendorff. And while a trade show hall might be a rather dreary venue, the exhibition’s title announced a new departure across the broadest of fronts: “Von hier aus” – “From Here.” But why Düsseldorf? Firstly, because, in the early 19th century, the loss of what was once the Elector Palatine’s collection amid the turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars had inflicted a wound that never fully healed. For many of the old masters the odyssey ended in Munich, where they now constitute a pillar of the world-famous Pinakothek museums. But this painful experience taught the city on the Rhine an important lesson: Art is identity. And that realization continues to make itself felt, even today. Secondly, because Düsseldorf was a booming commercial hub and its prosperity was expected to be a good breeding ground for arousing curiosity and keeping it alive. The city has traditionally been a place where new ideas get off the ground; the resulting profit benefits both sides of the equation. And thirdly, because that kind of respect for the ever-new vagaries of art keeps patrons and collectors alert and on their toes: Werner Schmalenbach, for instance, expanded the Kunstsammlung NRW – the art collection of North Rhine-Westphalia – into a hub for the ideas of modern and contemporary art. Haus K20 – a building with a strikingly curved, gleaming black facade that houses part of the collection – enjoys international standing. Then there’s Julia Stoschek, whose collection documents her discoveries of the very latest contemporary art more or less in real time. The essence of art lies in change and awakenings, as the city’s collections demonstrate at every turn. So many have started out from here. Painters Peter von Cornelius and Friedrich Wilhelm von Schadow are a case in point: In the 19th century, their influence as directors led to the Electoral Art Academy becoming an intellectual center for German Romanticism and Classicism. Art historians even deem the Düsseldorf school of painting worthy of its own chapter. It wasn’t long before the landscape and genre paintings by artists from the Rhine were moving and delighting audiences from Moscow to Chicago. As a side effect, they also spread the reputation of a serious and demanding education that was very likely second to none. And this is the very place where, ever since, generations of painters and sculptors from all over the world have learned that the freedom of art has to be fought for constantly. They have been set an inspiring example by strong professors who, with their work as artists, challenge their students to develop new and individual artistic positions. Art comes from art. In Düsseldorf, they’ve known that for more than 200 years. And acted accordingly. From here, teachers like Norbert Kricke, Ewald Mataré or Karl Otto Götz opened up new perspectives for young art after World War II – perspectives that were bolder than anything that had gone before and ranged from conceptual art in its severest form to the release of totally unfettered abstraction. From here, a young avant-garde put the entire notion of art up for debate. From here, initiatives like ZERO, Fluxus, happening and performance art matured into artistic movements that shaped the image of a new era.

Günther Uecker covered chairs, a television set and a piano with undulating fields of long nails. Today his nail pictures are considered icons. Heinz Mack and Otto Piene let light and fire take charge of their color spectra and moving installations. And Joseph Beuys covered his head with gold leaf and honey, stepped onto a stage at avant-garde gallery Schmela and explained art to a dead hare. Oh yes, there was some funny stuff going on in those wild Düsseldorf years… Daniel Spoerri invited his artist friends to a meal accompanied by wine and coffee and full ashtrays and hung what was left of it on the wall as a picture – thus inventing Eat Art. In a way, the industrialist’s wife, patron and collector Gabriele Henkel emulated him: She decked her table for anybody with money or wit or talent, a great figure or a good story to tell, held soirees, dinners, parties, orgies and happenings, brought people together, networked, made discoveries, nurtured and celebrated her protégés – and could always be found in the thick of things, reveling in admiration as the queen of high society. And when a gallerist like Hans Mayer featured stars of the international scene such as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg or Roy Lichtenstein in an exhibition, the hard rockers of The Who were invited along to pound their guitars at the opening, and art historian Werner Spies had a hard time making his lecture heard above the noise. On other occasions, the festivities were accompanied by the electronic music of Kraftwerk – a band from Düsseldorf. Gallerist Mayer, originally from Swabia, isn’t lacking in local pride, either: “Since the 1960s and ’70s,” he says, “Düsseldorf has been on a par with cultural capitals like New York or Paris as far as young art is concerned.” Two years ago he celebrated his gallery’s 50th anniversary, and to this day he is still almost permanently on the move between Hong Kong and Miami Beach, Paris, Madrid, Hamburg, Cologne and New York. Besides establishing and mentoring collections, his mission also includes attending the major art fairs, where he demonstrates that, in Düsseldorf, things that can only be had on their own in other capitals of young art are not only interlinked but synergized: A school, an environment marked by prosperity and learned openness, the trauma of a loss that continues to make itself felt, a dense network of magnificent collections and a public that can hardly wait to see what the next exhibition will bring. “Did I say on a par?” asks the gallerist, coyly batting his eyelashes. “Actually, that’s putting it modestly!”

Berlin might have become the capital and you could say Cologne is a little more laidback, but Düsseldorf has its academy and a mentality that not only emerged from it but continues to shape its thinking to this day. Ulrich Rückriem, Katharina Fritsch and Klaus Rinke, Gotthard Graubner and Sigmar Polke, Rosemarie Trockel, Gregor Schneider, A. R. Penck and Felix Droese, Nan Hoover, Imi Knoebel and Thomas Demand: The list of not just successful but famous graduates and teaching staff goes on and on. Many of them set out from here, captivated audiences, museums and collectors all over the world – and eventually picked up as teachers where they had left off as students: That’s the Düsseldorf school for you. No serious exhibition on the art of the last 20, 30 or 40 years, no Biennale, no Documenta and no sizeable museum show is complete without it. And because it just so happens that art always comes from art, the list of names continues unbroken: Peter Doig and Marcel Odenbach, Richard Deacon and Katharina Grosse, Tony Cragg, Rita McBride and Eberhard Havekost. Joseph Beuys was the most famous of them all. He was also the most conspicuous, the most controversial, and second to none when it came to fighting to overcome the forms and rituals of established art – all while adhering firmly to the Düsseldorf principle of training students through the medium of good and strict teachers. It was from here that he gave the world the “Fat Corner” and the “Felt Suit,” from here that he declared direct democracy and referendums to be artistic techniques and elevated everyone to the status of artist. When he started getting serious about his new concepts and occupied the offices of the already hopelessly overcrowded academy with would-be students who had been rejected, it was none other than the minister-president himself, Johannes Rau, who threw the recalcitrant professor out. The art scene had its scandal, and it fuelled the discourse on art for many years to come. One year later, in October 1973, Beuys wrapped himself in an old army coat and had himself rowed back across the Rhine in a theatrical happening that involved him standing upright like a conquistador in a dugout carved by his student Anatol. Even painters of the old school would be hard put to create images of such power. It was also from here that Korean-born Nam June Paik kicked off the phenomenon of media art with installations consisting of video screens full of flickering images. He was a professor at the academy for almost 20 years.

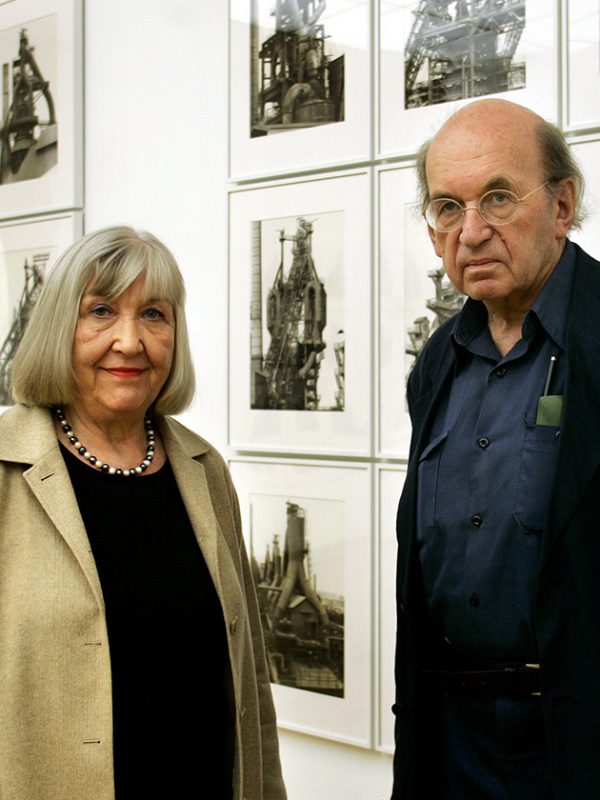

And to this day, Düsseldorf is a must for for anybody who wants to experience how art is expanding its boundaries and tapping into new media. With their austere, breathtakingly disciplined series of documentary images, Bernd and Hilla Becher established a school of photography whose alumni – Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth – have been at the very top of the international league for decades. And who, of course, have long since become teachers themselves. So if the Düsseldorf academy is a place where a great history has stayed alive, it’s certainly well worth stepping through the humble entrance on the side of the building and into the long, quiet corridor for a moment to get an inkling of just how much weight this history has. Even at the end of the 19th century, during the days of the German Empire, the people of Düsseldorf already knew how lucky they were to have their academy: They built a palace for it. The noble Renaissance-style building might turn its back on the city, its bars and galleries, its magnificent art collections and the Art Society, but by doing so, it ensures that the teachers’ studios behind the elongated facade are filled with the cool and mild north light that any tradition-conscious artist rejoices in. However, if the academy is an exemplary model of education, it’s always worth keeping an eye on what the latest generation of students is up to as well. Every February, 45,000 visitors do just that when the students and teaching staff throw open the doors of their studios to the general public. Many a museum of modern art would be more than happy to attract that many visitors in a whole year. So anybody who wants to know what art has to say to its present will find plenty of answers in Düsseldorf: both in the crush around the latest talents and from those who have already successfully put their positions up for debate in galleries – Bosnian media artist Danica Dakić and her search for a sense of home and identity or Sven Kroner and his ironically colored landscapes being two cases in point. Every single one of them has a place from which they can conquer the world of art: from here.