Telling Stories with Monuments by Helen Barrett | 6th December, 2019 | Personalities

One of the most successful architects of our time, David Adjaye is known for controversial, complex projects. His next challenge is The Abrahamic House in Abu Dhabi: a Catholic church, a synagogue and a mosque in the heart of the conflict-ridden Middle East.

Sir David Adjaye is remembering an early project: a modest house in east London. Today, one of the world’s most imaginative and sought-after architects winces as he recalls a “bruising” skirmish with London planners. “I was forced to take down the cladding. I was going to get a criminal record because my clients had no money and I had signed off the building.” He is clearly still exasperated by how, as he perceives it, the ambition of his younger self was slapped down. “The system reacts to try to discipline you in an infantile way, instead of understanding that you have pushed something.”

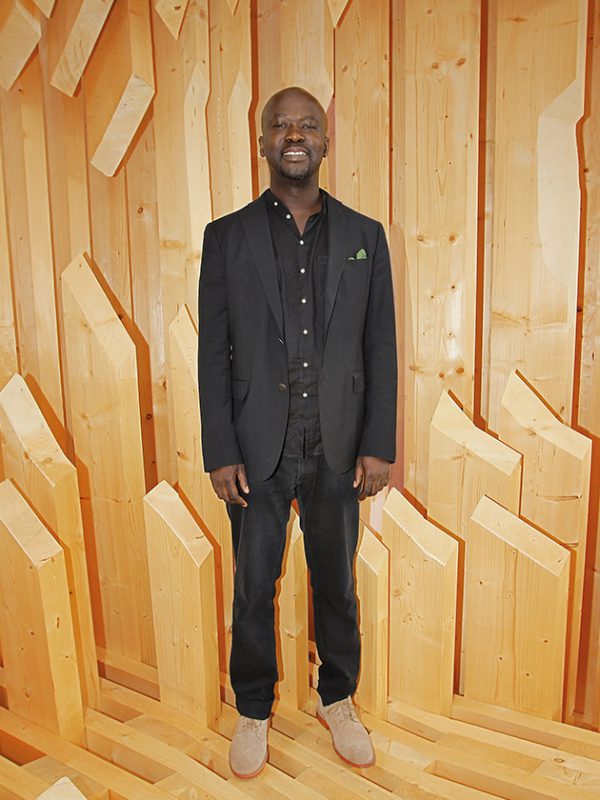

Whether working on a house or a grand civic project, for architects, he says, “controversy is normal.” Adjaye, who was knighted by Prince William in 2017, is not afraid of controversy nor complexity – and in terms of the scale of his work, he is still pushing. The 52-year-old British- Ghanaian – an assured, lean figure in black hoodie beneath black blazer – was celebrated for three months in the spring of 2019 at the Design Museum in London. His exhibition “David Adjaye: Making Memory” showcased seven of his public projects and set out his polymathic approach to work.

The projects on show were worlds away from east London family houses. They included the acclaimed Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington D.C., inaugurated by President Barack Obama just before he left office in 2016, and the new – and more divisive – National Cathedral of Ghana. Adjaye’s plans for a holocaust memorial and education center outside the Houses of Parliament in London were also on show. The exhibition explained his forensic approach to memorializing the past. Adjaye talks of “narrative” and “storytelling” as he describes how he draws on history, art, anthropology and memory in the hope of crystallizing human experience in the form of a building. The cenotaphs, statues and memorials that litter the public realm, the exhibition suggested, should be consigned to the past. “A monument with an epitaph, with the statement made on it, with the object representing it as some kind of structuralist concrete fact, has gone,” says Adjaye. “The point is not to be literal, but to be experiential. I’m not speaking to the writers of history any more, but to the zeitgeist.”

The Smithsonian structure, winner of the 2017 Beazley Design of the Year, is a good example. The building attempts to mark the African-American contribution to U.S. history with an ironwork façade echoing metalwork created by Creole African-American slaves in New Orleans and Charleston. The building’s threetiered form echoes the crown worn by a figure by Olowe of Ise, the early 20th-century Yoruban sculptor from Nigeria.

“I’m very interested in clients who have a strange site that has a difficulty.” DAVID ADJAYE

The $100 million cathedral in Accra is more problematic. It draws on Christian architecture an Akan motifs, and was built on government-gifted land. Critics have accused Ghana’s president, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, of blurring the role of church and state and prioritizing Christians over Ghana’s Muslim population. The lack of consensus over the cathedral illustrates two problems with Adjaye’s narrative approach: Stories conflict, and they change over time.

How does he decide which cultural references to put into a prestigious public project – and which to leave out? “Yes, I am editing. And you could argue, what gives me the right to edit?” he says. “My clients have every right to say no and fire me at any point. But my job is to make sure that I’m making forms that make sense to them, and communicate many possibilities.”

Adjaye acknowledges that he cannot satisfy everyone: “There’s no way. Even with the Smithsonian, I can’t please everybody. But what they are all looking for is an intellect that makes sense.” The best he can hope for, he says, is to deliver that. “Whether it does it right or doesn’t, that’s my burden.”

His next big project is very unique. He’s building a mosque, a synagogue and a church on an island off the coast of Abu Dhabi in the UAE. The opening of the multi-faith site is planned for 2022.

Adjaye always wanted to make public works. He made his name in the 1990s and 2000s designing homes for voguish figures of the day, such as Ewan McGregor and Alexander McQueen (houses were a stepping stone, he says, and he still designs them). “As a young architect, you are not given a public project for a long time until you have made some sort of reputation.”

His most distinctive and ambitious residential homes show early traces of the narrative process. The Dirty House in Shoreditch, for example, completed in 2002 for artists Sue Webster and Tim Noble, with its blank and blackened windows, emerged from “a whole discussion with the clients about creating beauty out of the detritus of the street.” How does he choose his clients? “If you want a very tasteful, elegant thing you’re not going to come to David Adjaye,” he says. “I’m very interested in clients who have a strange site that has a difficulty. Those are the projects I gravitate towards, and those are the kind of clients that gravitate towards me.” He prizes open-minded clients without a “prefixed image” of the final structure. “It doesn’t have to be dramatic. It can be completely mundane but it has to be something that’s a part of you.”

After dealing with multiple challenges and vested interests on major civic works, he talks of his small-scale planning skirmishes today in terms of intellectual challenges; “puzzles” to be solved, rather than the traumatic encounters of the past. He mentions another “enjoyable” recent project, where he worked with London authorities to build a house on an infill site. How does Adjaye get along with planners these days? “Well, it used to be terrible. They used to want to take me to court. Now they turn to me for advice.”