The Mediator by Martin Tschechne | 3rd June, 2022 | Personalities

For the first time in its 43-year history, the Pritzker Prize has been awarded to an architect from Africa. Diébédo Francis Kéré was born in Burkina Faso – one of the poorest countries on the planet. Social architecture, sustainable buildings and compound design are his focus and meant to create a sense of community.

He returned to West Africa, to his place of birth in Gando. Could hardly wait to give the tiny village in Burkina Faso what it so badly needed – it’s own school. At the young age of 7, he had had to leave his parents, his siblings and his home when his father sent him, his eldest son, to stay with relatives and attend school in the city. The schoolhouse there was close and stifling, like a furnace. Burkina Faso is one of the world’s poorest countries, ranking 182 of 189 on the United Nations Human Development Index.

In 2001, while still a student of architecture at the Technical University in Berlin, Diébédo Francis Kéré set off for Africa. He went to build a school so that the children in his village would finally have a place to learn to read and write – an elementary school where they wouldn’t fall asleep in the searing spring and autumn heat nor be swept away by the torrential summer rains.

It didn’t take that much at all: three flatroofed structures made of red bricks covered by a single tin roof that curved into the airstream like an airplane wing and, held up only by thin metal rods, appeared to be floating. Looking at it, some might recognize an affinity with the buildings of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose Neue Nationalgalerie museum is just a short distance from the university classrooms and studios in Berlin. But the primary school in Gando is much airier than that classic example of international modernism – it’s more economical and thus more suited to our time.

“Those are very cheap rods you see under the roof,” explains Kéré. “They’re reinforcing bars, the ones that usually disappear inside concrete to strengthen it.” The construction still manages to channel the wind, which passes across the masonry roofs, cooling the classrooms to a downright luxurious temperature. And it does so entirely without air conditioning, without electricity out of the wall.

So the architect who won the Aga Khan Prize in 2004 completed his first project before he’d even earned his degree. “Ultimately, I began studying architecture because I wanted to learn how to build,” he once said in an interview with the broadcaster Deutsche Welle. “But I was lucky to have such good professors in Berlin.” Professors like Peter Herrle or Ingrid Goetz who urged him to finish his studies and earn a degree. Later, he became a sought-after teacher himself: at the Technical University in Munich, at Harvard, Yale and the Swiss Architecture Academy in Mendrisio.

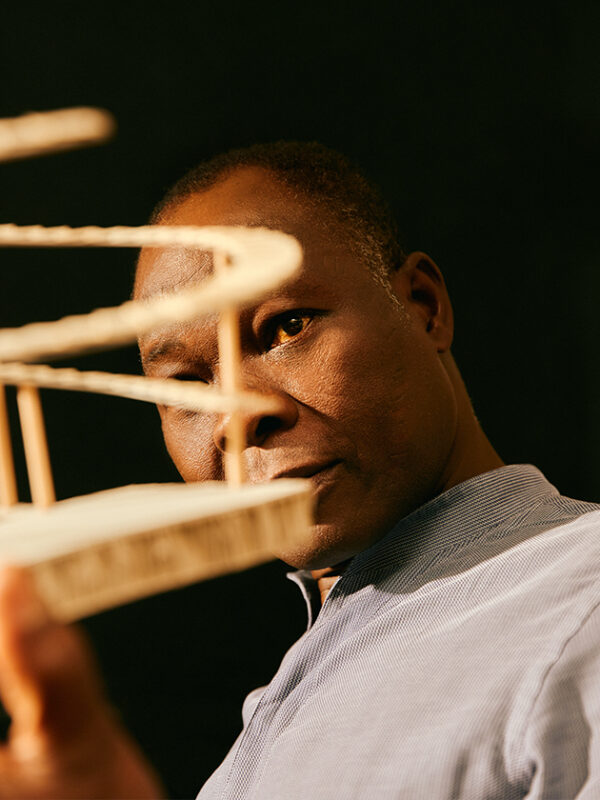

Francis Kéré (as he is generally known), was born in 1965. He is a slender, elegant man who moves with ease and deliberation; his features are relaxed. When he gives talks – and he often gets up on a podium to describe his work – he captivates audiences with his charming, friendly manner. He likes to tell the story of the women in his village who used to fumble a few coins from the folds of their dresses when he set off for the town again as a small boy. Or that of the seven or eight laborers from Gando who joined him in jumping up and down liken children on a brick masonry arch to demonstrate its strength despite the fragility of it construction. There’s even a photo, and all of them are laughing. Moments like this give a fine intimation of Kéré’s high energy and sense of purpose.

In March, the Hyatt Foundation in Chicago awarded him the coveted Pritzker Prize, a kind of Nobel prize for intelligent and innovative architecture and design. The distinction put Kéré in the same league as SANAA, Herzog & de Meuron, Sir Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas and Tadao Ando. In a statement full of respect but also resonating with sheer amazement, the jury wrote: “He knows from within that architecture is not about the object, but the objective; not the product, but the process.”

In any case, the primary school in Gando was just the beginning. It would be followed by teachers’ housing, an extension several years later and a school library in 2019. A secondary school for older students is currently under construction too. According to Kéré, 80 percent of the inhabitants in his village used to be illiterate, including his own father. But the number of students has meanwhile grown from 120 to 700. It’s difficult to express architectural success more strongly. And it was a community effort right from the start. The people in his village understood what the prodigal was offering.

While still in Berlin, and with the help of his fellow students, Kéré used crowdfunding to raise the necessary money; only a modest sum was needed for this transformational project. And if any of the villagers were still unsure about the architect’s intentions, Kéré, the orator, put their doubts at rest. After all, he was the son of the village elder, and the first to be sent to an unfamiliar place in order to attend school.

Lined up in procession, men, women and children helped to haul the clay, mix it with cement and fire it into bricks; they compacted the ground to the rhythm of their tradition, all working together, using wooden tampers and their feet, brushing it smooth and polishing it with stones until it was a soft as a baby’s bottom.

Kéré, his shirt casually untucked, takes a few dance steps in demonstration: That’s how they compacted the earth. As if taking part in a festive celebration. The choice of building material was self-evident: Gando’s bare, sparse surroundings provide nothing but clay and red sand. And perhaps some tough eucalyptus wood. Kéré made it into a principle: Location determines material. Local quarry stone for the Startup Lions Campus (2021) on Lake Turkana in Kenya, cast clay for the Burkina Institute of Technology (2020) in Koudougou.

For the Tippet Rise Art Center in the northwestern state of Montana in the U.S., the architect used slices of timber that foresters had discarded, in other words scrap wood, to build the Xylem pavilion (2019), a meditation and gathering space whose design references and is modeled on traditional structures in Dogon culture in Mali, West Africa – and whose building material grew within sight of the pavilion. “No healthy tree was felled or otherwise damaged for this project,” Kéré stated. At the same time: Austerity doesn’t just teach pragmatism. It cultivates respect.

This is the dual message that Kéré formulates in all of his projects, be it a shelter at the head of a trail in the Rocky Mountains or a parliament building in his home country, the monumental structure of which palpably conveys to his fellow citizens what it means to participate in a democratic process: our parliament, our country, our future.

Regardless of where his buildings are located – in Mali or Mozambique, Montana or Miami, London or Weil am Rhein in Germany, and regardless whether a structure was built to provide temporary protection and shade to festivalgoers in California or ensure longterm medical care in a bitterly poor country, the message is always the same: Architecture arises from within a community and its purpose is to serve it. Also: Architecture has a responsibility to preserve the balance in nature, the sustainability of resources and the future of our climate. Producing cement already causes eight percent of global emissions of greenhouse gases. Aesthetics follow function. And thoughtful consideration.

That’s a surprisingly self-effacing attitude for a top-league architect – but it’s one that also points the way forward for the future of the trade. Humility as opposed to monumental pomp, commitment to community rather than gestures of triumph. And a sense of responsibility toward form, which for far too long has reflected personal pride instead of servinga collective need.

Kéré spends a good portion of his time surrounded by computer screens and cardboard architectural models in the light-filled rooms of his office in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district. His face bears the ritual scars from cuts performed on his skin as a child. He came to Germany as a young man of 20 to learn the cabinetmaking trade in 1985, started university ten years later and ten years after that, in 2005, opened his own architecture firm in what used to be a workshop in a rear courtyard building – right here at Arndtstraße 34.

These days, Kéré has a good dozen employees. For years, he has been a dual citizen of Germany as well as Burkina Faso. He pulls out a photograph. It shows a large group of perhaps 40 or 50 people beneath a large tree somewhere in Africa. They’re wearing loose, colorful robes, their heads wrapped in scarves. Many of them have come by bicycle. They sit close together in the long shadow of the afternoon. Explaining the ancient principle, Kéré says: “You come together and sit down to discuss the affairs of the community. That’s the beginning of true democracy.”

What a model for architecture! In the summer of 2017, this same kind of tree emerged amid the greenery of Kensington Gardens – an enormous structure with a shining crown of steel and wood and transparent panels that protected those beneath it from the rain, provided shade from the sun and let in the light just like regular foliage. And since London is not in Africa, the architect surrounded his temporary Serpentine Gallery pavilion with four segments of protective wall, as dark blue in color as the African night but open enough to make the gathering space accessible from all sides.

The National Assembly building for the capital Ouagadougou was a similar project, one where every visitor would experience his orher own share of the community. During the “Black Spring” of 2014, when the people of Burkina Faso rose up against their corrupt political elite, the old French colonial building burned to the ground.

Kéré took advantage of the moment and the empty space to design a huge pyramid with views over the surrounding countryside. It had terraces covered with greenery, exhibition spaces and market stands, and was accessible to all. This design may still exist only on paper, but with this project, the architect nevertheless grabbed the opportunity to build a new political culture in the poor and so often humiliated country of his birth. “I hope to bring about a paradigm shift,” he says, “and encourage people to dream and take risks.” Kéré is a fighter.

Perhaps it was his collaboration with the late German theater director and performance artist Christoph Schlingensief that led Kéré to the realization that even the most carefully considered sensitivity to local conditions and global dangers requires a degree of orchestration if you want to convince audiences, users and the general public of your intentions in this respect. Until his early death in 2010, Schlingensief was committed to the project they were working on together: an opera village some 30 kilometers from Ouagadougou, the capital, a village where everything would come together: fine art and health care, architecture and literacy programs, African film and sustainable agriculture, classical opera and the first cries of a newborn child.

The opera house itself still hasn’t been completed, but other houses and studios around it are already filled with life. It’s a culture center without a center, but still a place in which to forge something like an identity, to take pride in one’s roots, even as a citizen of a country that ranks 182 on the global prosperity index. “Everyone deserves quality,” the architect ninsists, “everyone deserves luxury, everyone deserves comfort.” That’s precisely why he punctuated the roof of the school library in Gando with circular openings, rings cut from clay pots that belonged to village residents. These pots without bottoms or lids provide agreeable light from above and allow the air to circulate – as well as creating a visible connection to everyday village life.

This is also why the Lycée Schorge Secondary School, located on the outskirts of Koudougou, is built like a kraal around an open yet protected gathering place. And why Kéré based the structure of the Surgical Clinic and Health Center in Léo on a traditional village of clay houses. Defining one’s own center is the intention behind it. And the National Assembly building that is currently under construction in Porto-Novo, the capital of neighboring Republic of Benin, is based on its role model – the giant African Palaver tree.

The Pritzker Prize has been conferred on an outstanding architect or architect duo every year since 1979. As incredible as it may sound, Diébédo Francis Kéré is the first African architect to be honored with this distinction. And not only that: He is the only living architect in Germany to have been granted the prestigious award.