Boundary Crosser by Steffi Kammerer | 2nd September, 2022 | Personalities

She is the avantgarde star of the scientific world. Using nature as her guide, Neri Oxman explores the intersection between technology and biology in her search for sustainable solutions for the future.

Life and death, nature and technology are all interconnected in Neri Oxman’s work. The versatile Israeli-born architect, designer and artist is changing the cities of the future from her laboratory in New York.

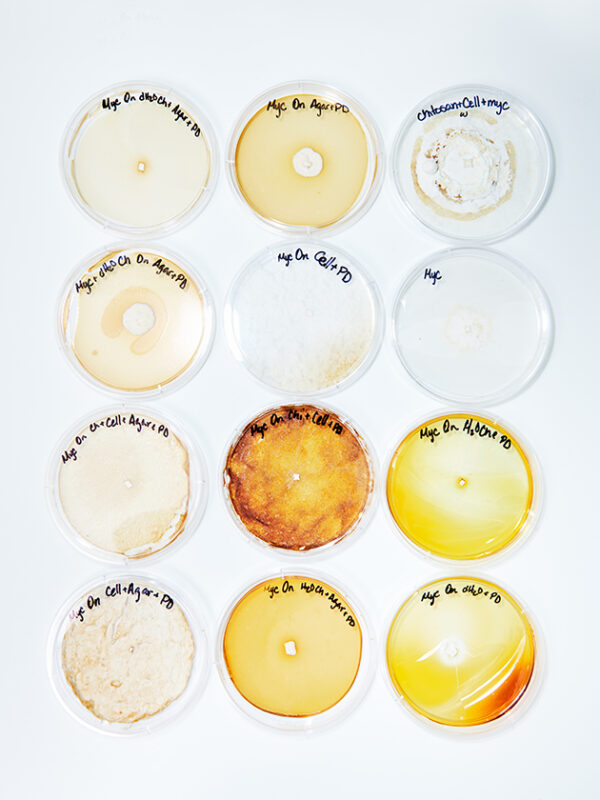

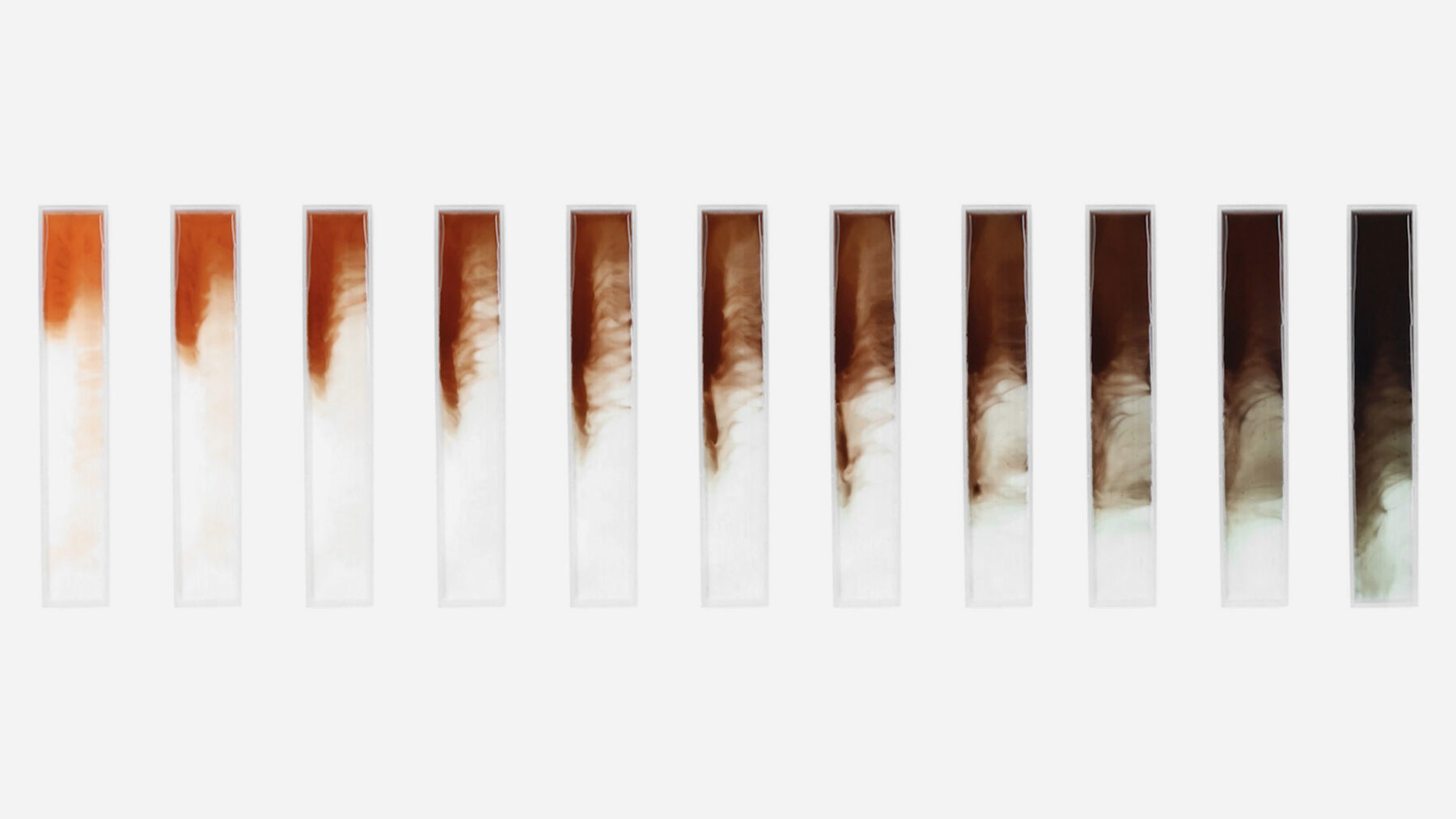

Ants that communicate with each other when building complex tunnels; intricate paper nests constructed by wasps; birch bark that protects trees from the sun and from fluctuating temperatures: These are the type of phenomena that fascinate Neri Oxman and from which she draws her conclusions. She compares concrete columns of uniform thickness with the trunks of palm trees, which are less dense on the outside than at the center, and then invents a 3D printer that can cast variable thicknesses of concrete. Nature is her model, but Oxman doesn’t imitate it, she makes computations, creates new things and considers scalability.

Oxman spent the majority of her childhood in her parents’ architecture studio in Haifa and in her grandmother’s garden. There, surrounded by fig and olive trees, the little girl watched the clouds, and developed her deep connection to nature. Oxman’s parents are both respected architecture professors, and Neri and her sister grew up in a household where design was part of everyday life. After completing her military service in the Israeli army, she began medical school but after two years switched to architecture, which she studied in Haifa and London. She earned a PhD at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, where, shortly afterwards, she was offered a professorship.

In 2015 Neri Oxman held a TED Talk that so far, has been viewed nearly 2.8 million times. In it, she talks about how nature offers custom-made solutions, not uniform ones: “Our facial skins are thin with large pores; our back skins are thicker with small pores. One acts mainly as filter, the other mainly as barrier. And yet, it’s the same skin, no parts, no assemblies.” Nature differentiates and demonstrates flexibility, whereas humans come up with standardized objects that are industrially produced.

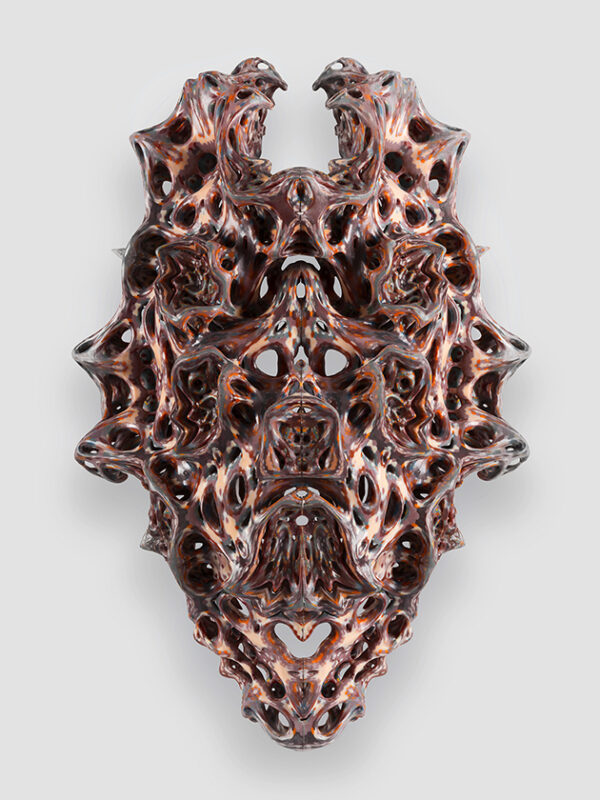

Oxman’s life work, at 46, would easily fill three lifetimes. What she does is just as hard to categorize as Oxman herself, because she does so many different things, from creating highly esthetic objects to inventing robots that can print a house. In 2018, she won the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award for interaction design. Jenny Lam – one of the judges and a leading designer at Oracle – said Oxman could just as easily have been nominated for fashion design or product design, and regards the artist as a present-day Leonardo da Vinci. Oxman regularly introduces her projects on the world’s biggest and most influential platforms: the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Smithsonian Design Museum or, two years ago, MoMA in New York, where she had a solo exhibition entitled “Neri Oxman Material Ecology.” Material ecology is her name for the discipline she established. It describes the fruitful union between ecology and the artificial world.

For the MoMA exhibition, Oxman continued the silkworm project she had been working on since 2013. The result was a giant pavilion, six meters high and five meters wide, spun by over 17,000 silkworms whose productivity had been boosted with the aid of computers and robots. Unlike in conventional silk production, not a single larva died. The combination of technology and biology makes this possible.

Oxman’s breadth of thinking is enormous, she sets her mind to exploring, rethinking and recreating just about everything. Her vision is to create buildings whose facades can adapt to changing weather conditions as well as to light; building parts that can regenerate themselves like the cells of the human body, or, alternatively, can be programmed to disintegrate after a specified period when they are no longer needed.

As early as 2014, Oxman created wearables containing living organisms within them. Her goal: to set in motion synthetic biological processes that could one day enable humans to survive on other planets by transforming solar energy into sugar, for instance.

Six years before that, in 2008, she already ex- pressed what she saw as a unique opportunity. At Burda’s annual DLD (Digital, Life, Design) conference in Munich, she said: “We are going to a new period, a new paradigm in design,” away from serial production and the repetitions of the machine age and toward the new possibilities offered by the digital age. “Now we can work with difference and differentiation. We can begin to inform the way we design spaces and products and experiences to be custom fit and continuously changing and adapting.”

Four years ago, Oxman involuntarily entered a very different kind of limelight when the media spun a story connecting her romantically to Brad Pitt. At the time, however, she was in a relationship with the investor and hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, now her husband, and in the spring of 2019, she gave birth to their daughter. Another important development: After about 10 years of teaching at MIT, Neri Oxman has opened her own design and research laboratory in Manhattan. Stay tuned!