The Architecture of Life by Silke Bender | 6th December, 2019 | Offices

If the 20th century was the century of physics, the 21st belongs to biology. So says architect David Benjamin, who’s pinning his hopes on bricks made of mushroom cultures and plant waste. At The Living, his interdisciplinary studio in New York, his work ranges from developing the intelligent and organic city of the future to improving airplanes. An encounter with a man of many talents and unlimited imagination.

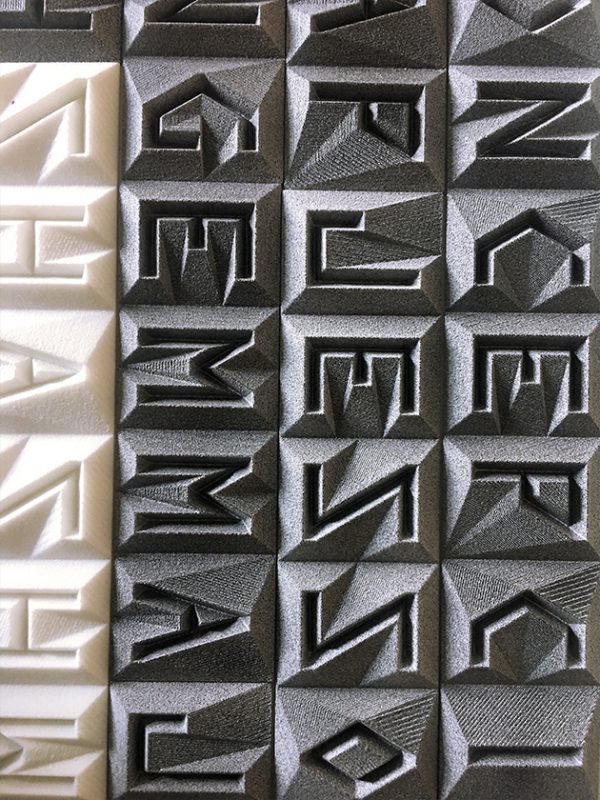

The La Fabrique du Vivant exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris came to an end in April after presenting the world’s most innovative positions in science, design and architecture. In the digital age, design is increasingly interacting with the natural sciences. This is something that raises questions, such as: Can life be programmed? And if so, how? One of the most intriguing participants in the exhibition was New York architect David Benjamin. At first glance, the archway he built for it out of “Living Bricks” looks like it’s made out of white blocks. But appearances can be deceptive: The bricks are in fact living organisms, made out of shredded corn stalks and other agricultural waste that’s been alloyed with living mushroom mycelium. That sets a natural welding process in motion: The bricks grow together into a lightweight but stable structure. When the mushrooms are no longer supplied with water, the structure stops growing and assembling itself.

The archway in Paris was a miniature version of the spectacular Hy-Fi tower that Benjamin’s firm presented at the MoMA PS1 in New York in 2014. Consisting of three open cylinders, the 13-meterhigh structure was the centerpiece of the Queens museum’s courtyard for a whole summer. Hy-Fi was the first large-format structure to use the fungus-based technology – and the 10,000 bricks needed to build it were cultivated in just five days. “That illustrates the standard I’ve set myself: Everything we produce in future should be able to return to the natural cycle as sustainably and with as little impact as possible,” says Benjamin.

When the 45-year-old founded The Living in 2006, he did so with the self-confident intent of “creating tomorrow’s architecture.” He studied at Columbia University, where he now teaches as a professor. “Even when I was a freshman, I had the idea of expanding the definition of architecture,” he says. “I took an interactive approach and began seeing architecture through the eyes of biology, taking living organisms as my starting point. Maybe buildings aren’t just static objects, maybe they can be dynamic, living systems too.” In Asia, for instance, he implanted LED facades onto buildings and LED buoys into water, which react to air or water pollution by lighting up.

For a man with such wide-ranging interests as Benjamin, this interdisciplinary approach was a natural process. Today, the biologists, architects, artists and IT specialists who make up the 10-strong team at The Living work hand in hand. If you want to be future-proof, he believes, you have to learn to think across disciplines. The team started out in an old shipyard, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which is now a huge co-working space and research laboratory for robotics and nanotechnology. The Living only moved to downtown Manhattan last year, taking up residence in the former offices of the Cunard Line on Lower Broadway. The building is almost 100 years old, and the team is based on the ninth floor with a view of the Statue of Liberty from the windows. They have around 140 square meters of space for themselves on the “WeWork” floor.

The company’s startup and open think-tank character remains: Rather than shutting itself away behind closed doors, the innovative and meanwhile commercially successful firm shares its office space with 60 other creatives – who even double as guinea pigs for their prototypes from time to time. The area near Wall Street is changing from a financial district into a startup hub. Because a large number of banks and insurance companies have moved across the river to New Jersey in recent years, more and more co-working spaces are becoming available in the old office buildings they abandoned. “The way buildings are used changes over time, and intelligent architecture should be prepared for that,” says Benjamin, citing the Embodied Computation Lab, his new project on the campus of Princeton University: simple in form but sophisticated in function.

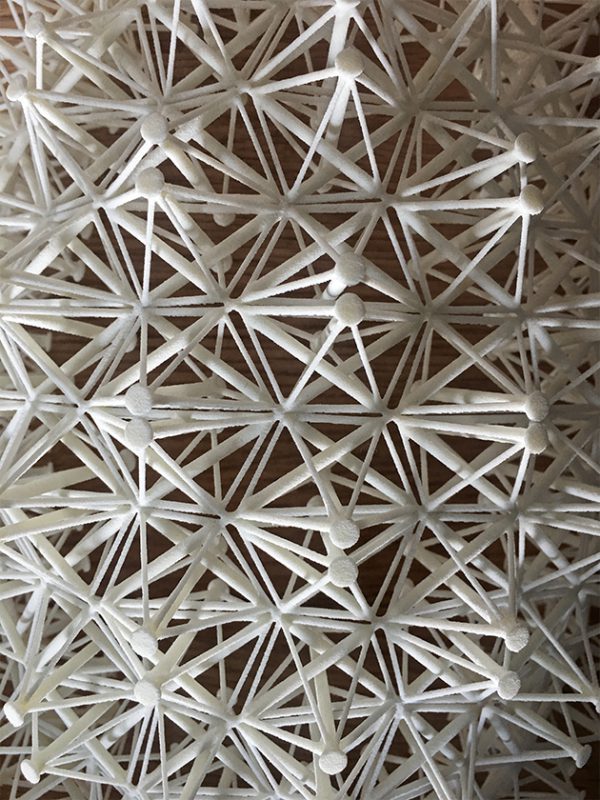

The students there today are working on new construction technologies and robotics. The cladding consists of reclaimed scaffolding boards. The planks were scanned so that their insulating properties could be analyzed on the basis of knots and grains, and then used accordingly. “My idea was to create a building that works like an open source program and translate the principle into hardware,” says Benjamin. “After all, 20 years from now, the students there will be working on robots and machines that we can’t even begin to imagine.”

Today his firm doesn’t just work on visionary architecture, art and environmental projects, but also for major European corporations like plane maker Airbus, on whose behalf The Living used computer-aided design to develop unusually lightweight components that result in much lower fuel consumption and carbon emissions. The “Bionic Partition” for aircraft cabins is currently in the test phase and is to be used in models of the A320 series. At the same time, The Living is building a new aircraft engine production facility for Airbus in Hamburg, slated to commence operations in 2020/21. The mushroom bricks are set to make their commercial debut this winter too – as an organic interior for The Solstice, a new farm-totable restaurant in New York’s East Village. And so the low-impact recycling chain that David Benjamin aspires to comes full circle: If interior design tastes change, the wall and decor elements can be used as compost where the vegetables the restaurant serves are grown: in the fields of upstate New York.